Before the latest rate rise, some lenders were reporting house price falls. But is this just a blip or the start of a bigger drop?

What happens when house prices fall?

Falling house prices have the biggest immediate effect on people who want to move.

Fewer properties are available and would-be movers, who already own a home, may have less purchasing power.

Meanwhile, first-time buyers may find that properties are more affordable, allowing them to get a foot on the ladder – assuming they can get a mortgage.

But a drop in prices can also send shudders through the finances of homeowners who are staying put.

At the most extreme, households can end up in negative equity – where the amount they have borrowed is greater than the current value of their home.

And with about a third of household wealth tied up in home values, falling prices can make people feel less secure, resulting in them saving rather than spending.

Less spending can make an economic slowdown even worse.

Why might a drop not turn into a house price crash?

On 3 November, the Bank of England raised interest rates by 0.75% to 3% .

It was the biggest single rise in the cost of borrowing since 1989.

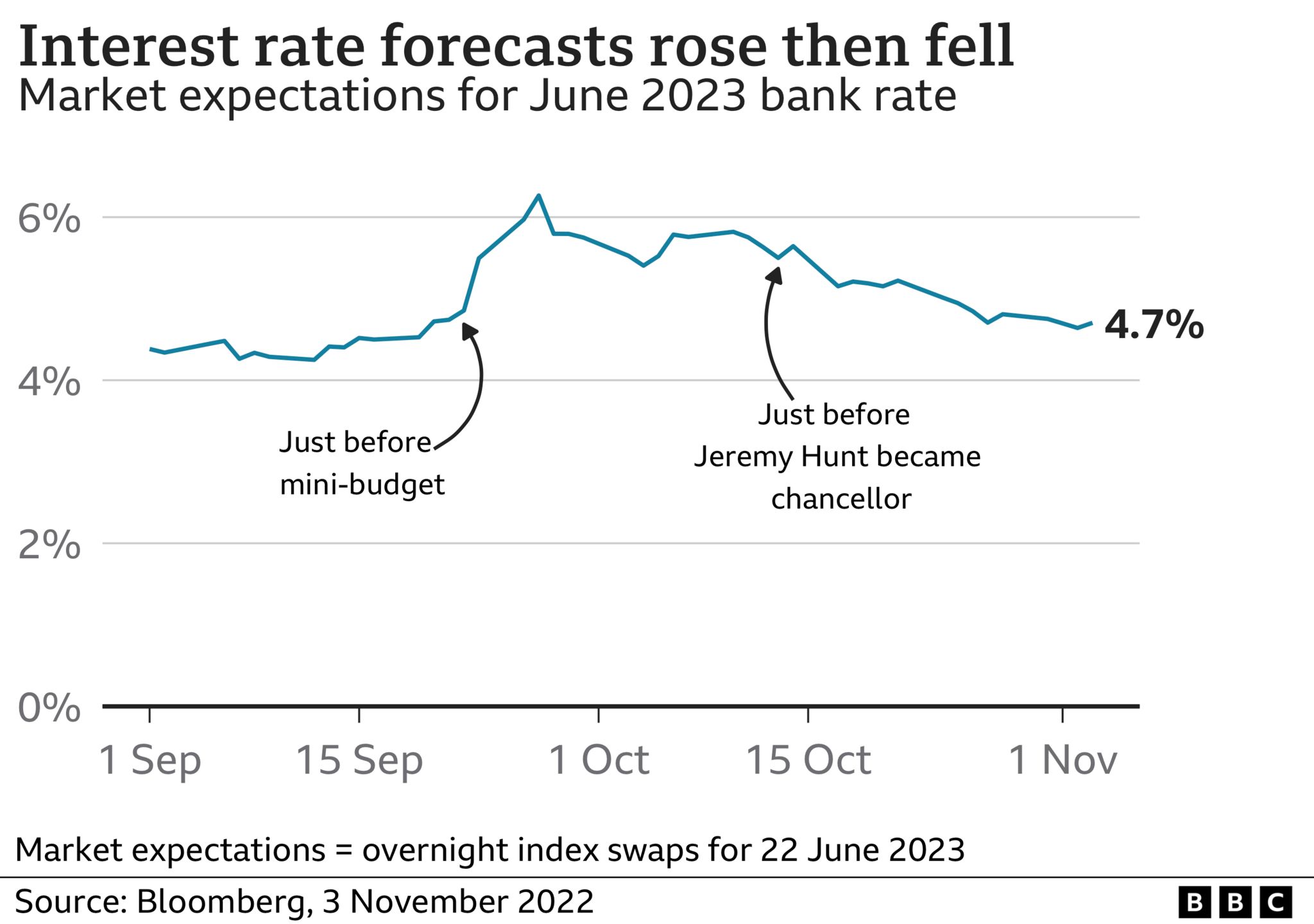

After the mini-budget, financial markets were forecasting that the Bank of England’s interest rate would rise above 6% in 2023.

However, traders now expect the peak to be under 5%. You can use the calculator above to see how big an effect those kinds of changes can have on monthly repayments.

In the early 2000s property boom, 100% mortgages and cashback offers were not uncommon.

But after the 2008 financial crash, mortgage lending rules were tightened.

As a result, loans leave more room for prices to fall before borrowers are stuck with negative equity. Most recent borrowers have also had their ability to pay checked against interest rates even higher than the ones we’re seeing at the moment.

At the start of the pandemic, when many people’s earnings were cut, banks allowed people to defer their mortgage payments for up to six months.

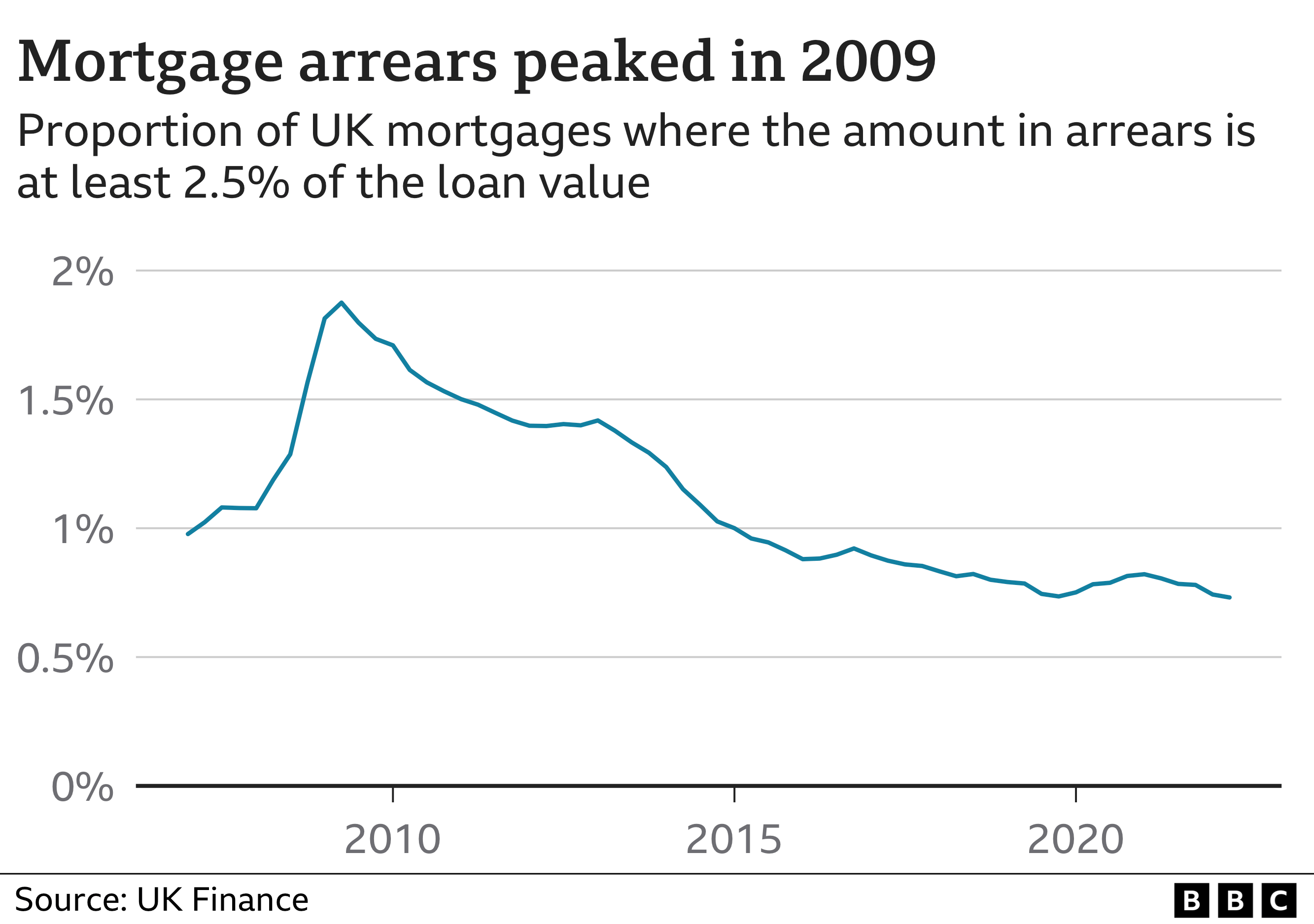

Repossessions were suspended from March 2020 to April 2021 and, even in the year since restarting, have remained below 4,000. That compares with more than 20,000 in the years just before the 2008 crash.

What has happened to house prices?

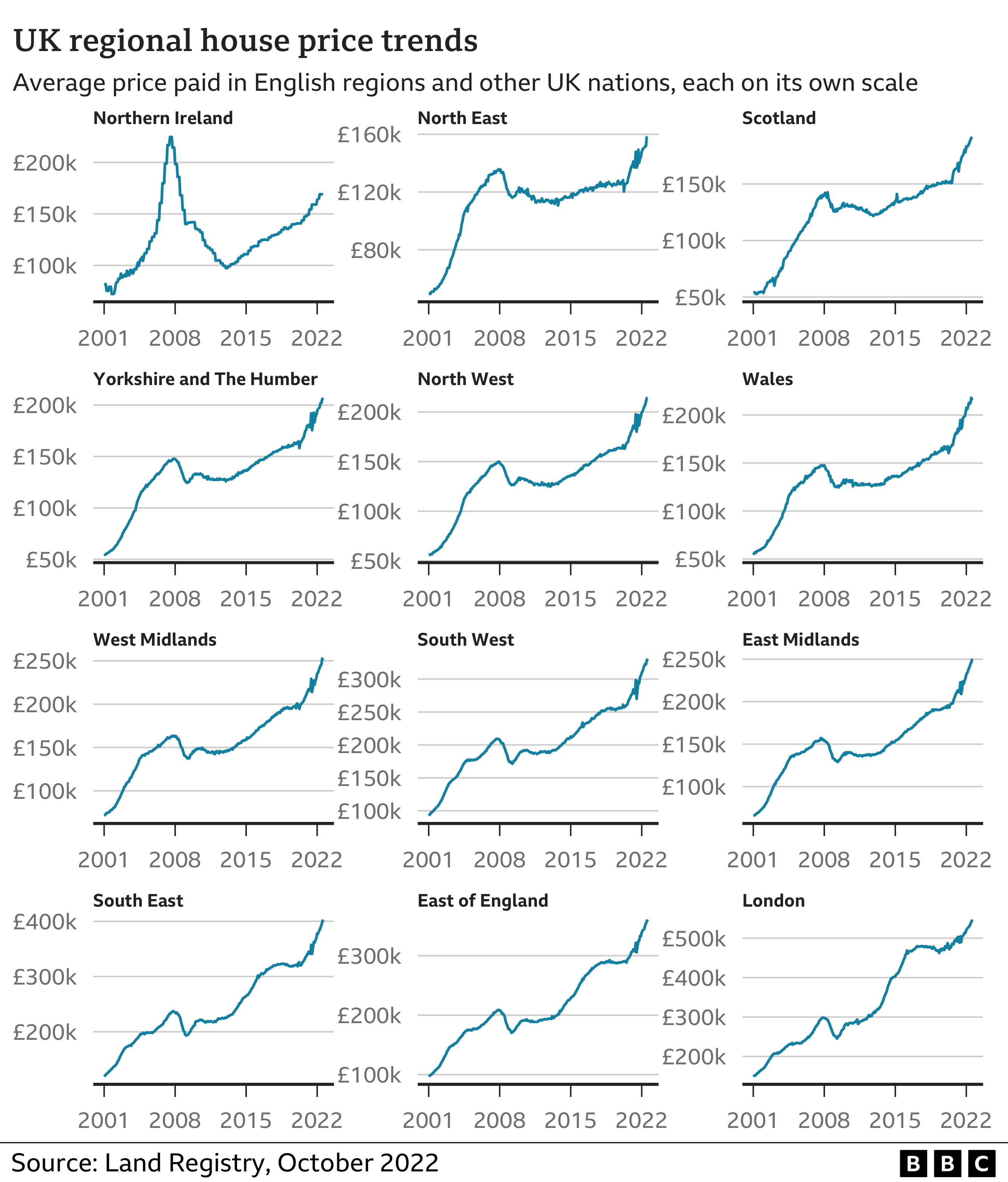

In the last two years, prices rose steeply – by about a quarter – across most of the UK.

That pace of growth is much faster than that seen after the 2008 global financial crisis, where houses lost about a sixth of their value and it took five years, on average, for prices to recover.

In Scotland and the north of England prices kept dropping for a few years – and stalling in Wales – meaning the recovery took longer.

In the north-east of England, prices only returned to their pre-crash levels at the end of 2020.

Meanwhile, in Northern Ireland, house prices still remain below their pre-crisis peak.

Recent price growth has been much slower in London than the rest of England, with prices dipping slightly during the pandemic. Despite this, the capital has comfortably seen the largest rises over the last 10 years as a whole.

Will house prices fall in the UK?

Data from Nationwide and Halifax, which give an earlier hint than the Land Registry figures shown above, have started to show month-on-month falls.

Monthly changes can be blips, but the UK’s largest lender, Lloyds, is planning for an 8% price fall next year.

Big jumps in interest rates put pressure on the amount people can afford to offer for houses, and that means less demand.

Some sellers may also delay putting their homes on the market. There have been fewer sales than in the year leading up to last summer’s surge in prices before the temporary stamp duty reduction ended.

But if interest rates stay high, an increasing number of people will come off fixed-price mortgages (about 100,000 each month) to new, higher rates.

Some home owners will find higher monthly payments unaffordable, making them more likely to sell.

The number of people in arrears peaked during the financial crisis, but has not risen significantly during the pandemic, helped by lenders granting payment holidays.

In the worst case, payment difficulties can lead to the bank repossessing someone’s home, although lenders try to avoid this. More than 200,000 were repossessed in the five years after the financial crash.

Mortgage affordability depends on other cost-of-living pressures like energy bills, wages and job security. The future of house prices depends on the economy as a whole.

The worry is that falling house prices and a stuttering economy start to reinforce each other.