Almost two million households will see fixed-rate mortgage deals end this year, with most facing the prospect of higher monthly payments.

What options do borrowers have?

What’s happening to mortgage rates?

About 20% of residential mortgage-holders have variable rate or tracker loans, totalling about 1.6 million households in the UK.

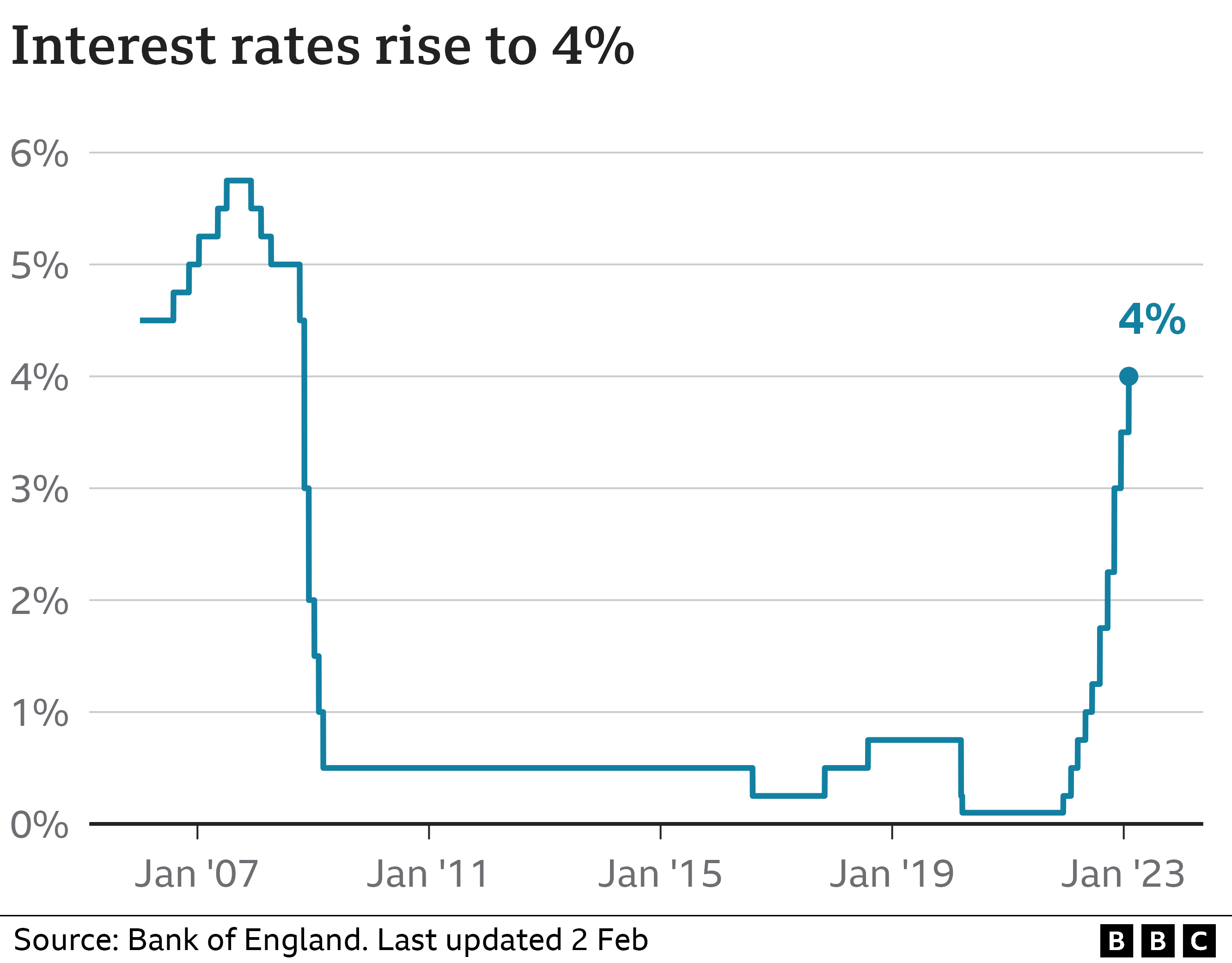

Their monthly repayment rises whenever the Bank of England increases its benchmark interest rate, which it has done ten timed in a row.

A typical homeowner on an average tracker deal now pays almost £400 more a month than in December 2021, when rates started to rise.

Fixed-rate mortgages are different. The monthly payment stays the same for the length of the deal – usually two or five years. About 78% of mortgage holders – some 6.5 million homeowners – have this type of mortgage.

When these deals expire, borrowers automatically move onto their lender’s standard variable rate (SVR), which tends to be much more expensive. At the moment SVRs are typically 7% or 8%.

It is thought that 1.8 million fixed deals will end in 2023.

At this point, the vast majority of borrowers take out a new fixed-rate mortgage with the same lender or a rival. About three-quarters use a broker to find a deal.

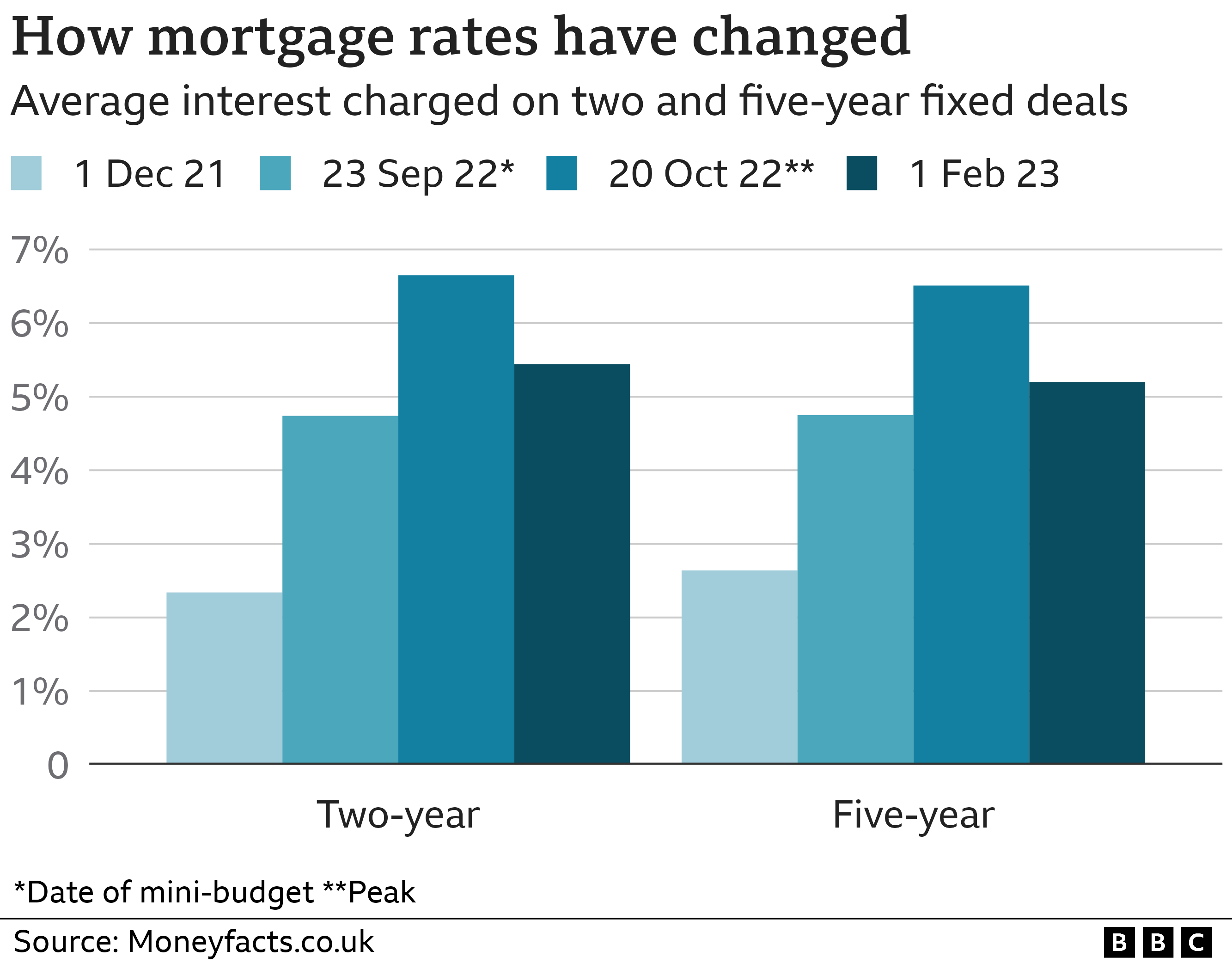

But the fixed-rate deals available now are much more expensive than they used to be. A couple of years ago, the best deals were at 1% whereas the best rates now are 4%.

Average rates – which had already been rising – soared after the September mini-budget, but have dropped back since.

Even so, many homeowners face the prospect of paying hundreds of pounds more a month on their mortgage repayments.

My deal is expiring, what should I do?

Dig out your paperwork, to check when your deal ends and your current interest rate.

Get organised. Lenders usually let you secure an offer within six months of the end of your current deal. It generally takes at least four weeks to complete a mortgage offer. Leave it too late and you could end up paying the more expensive SVR for a period between deals.

Look at your budget to decide what you can afford. Your income or circumstances may have changed since your last mortgage. The more complex your situation, the narrower the choice of deals, and the longer it can take to process.

Consider fees. Some deals have arrangement fees; some have exit penalties (called early repayment charges). Make sure you include these in your calculations.

Negotiate. If a lender announces lower rates after making you an offer but before your new deal starts, you can ask it to match the better deal.

It is possible to switch to a different provider offering a more competitive rate during this period, but it would require a new application.

Should I consider a variable rate as a stop-gap?

Many expect that the Bank of England’s benchmark interest rate – and, in turn, mortgage rates – will fall later in 2023.

It might be tempting to stay on your lender’s SVR while waiting for cheaper fixed-rate deals to emerge.

But one broker warns that an SVR is “not a cheap place to sit and wonder”. You might be better with a tracker rate. Trackers are also linked to the Bank rate – so fall if it drops – but can be more competitive than an SVR.

You need to decide what’s right for you, but some brokers argue fixed rates might not fall sufficiently to make any delay financially worthwhile.

Committing to a fixed rate – even at a higher cost – gives certainty for a set period of time.

What happens if I can’t pay?

Some people are already struggling to keep up with repayments. While arrears levels are still relatively low, the boss of HSBC warned the “headwinds are ahead of us, not behind”.

A pattern of missed payments can make it difficult to get a new deal, potentially leaving borrowers on the more expensive SVR.

Other unpaid bills, such as credit cards and utility bills, can affect your credit record, which lenders use to consider mortgage applications.

Check your credit file is correct before submitting paperwork. Brokers recommend you are upfront about your payment history.

You could consider extending the length of your mortgage term. For example, if your home loan is due to be repaid over 17 years, it can be restructured over 20 years instead.

That reduces monthly repayments, and might be a short-term option for some people. However, ultimately, it mean you pay more in interest over the lifetime of the mortgage.

Anyone who finds their income is higher than expected could use the extra money to overpay their mortgage. This would cut the total interest bill, and most lenders allow you to do so, up to a set level.